for COVID-19 testing. He works long hours and weekends. I don’t think he sleeps more than four hours each night. He is always ‘on,’ answering urgent work emails or rushing to get back on the job.

I worry about him, his health and his ability to continue going like this. I worry about what’s going to happen if he gets sick, maybe with COVID or from not sleeping or eating.

“I wish you would take better care of yourself,” I say, pushing the glass over another inch. He looks up from his phone and smiles.

“Now is not the time for me to take it easy,” he says. “There is not enough testing available. Now more than ever before in my career, I feel what I do makes a difference in people’s lives.”

I nod. I realize his schedule and the intensity with which he tackles testing issues are not sustainable. I want to help my husband take better care of himself, but at the same time, I am resolute not to discourage him from doing the right thing. Clearly, I am grappling with a dilemma.

So many others who are dealing with similar dilemmas. Thus far, COVID-19 has been cataclysmic for humankind, challenging us at the core and threatening our need for safety, continuity, and control. We may have lived and worked through 9/11, Hurricane Sandy, and other disasters, but most of us have never been through anything like this before. This virus has directly impacted a much broader population of the US than any other event over the last few decades, and its active status has been considerably longer than other disasters. (My intent is not to minimize other events, but rather to emphasize the ongoing risk and the “unknowns” associated with COVID-19’s current duration, not to mention the possibility of it returning in the not-too-distant future.)

As a psychologist and executive coach, I often think of ways in which leaders ‘show up’ in crisis. Working from home or on the front lines, isolated and with our usual work structures undone, we now face daily moral dilemmas and we turn inward in search of meaning. The leaders among us must search inside themselves, accessing their values and allowing these values to guide their actions. In times of crisis, there are innumerable ‘moments of truth’ when the decision made, informed by values or not, creates a cascading effect of multiple consequences.

Moral Development and Courage Under Fire

“I have learned that as long as I hold fast to my beliefs and values, and follow my own moral compass, then the only expectations I need to live up to are my own.”

– Michelle Obama at Tuskegee University, 2015

“Captain Brett Crozier, skipper of the nuclear carrier U.S.S. Theodore Roosevelt, was relieved last week from his command for warning the nation publicly of the Coronavirus crisis on his ship,” reads a letter by David Wakelin of South Portland, published by the Press Herald on April 6, 2020. “As a Navy veteran, I know that this means his career is ruined and over…He clearly knew that this would happen, and he proceeded notwithstanding. That is the definition of courage under fire in my book. In this perilous time, we need more people to “speak truth to power” and do the right thing even when the consequences will be serious.”

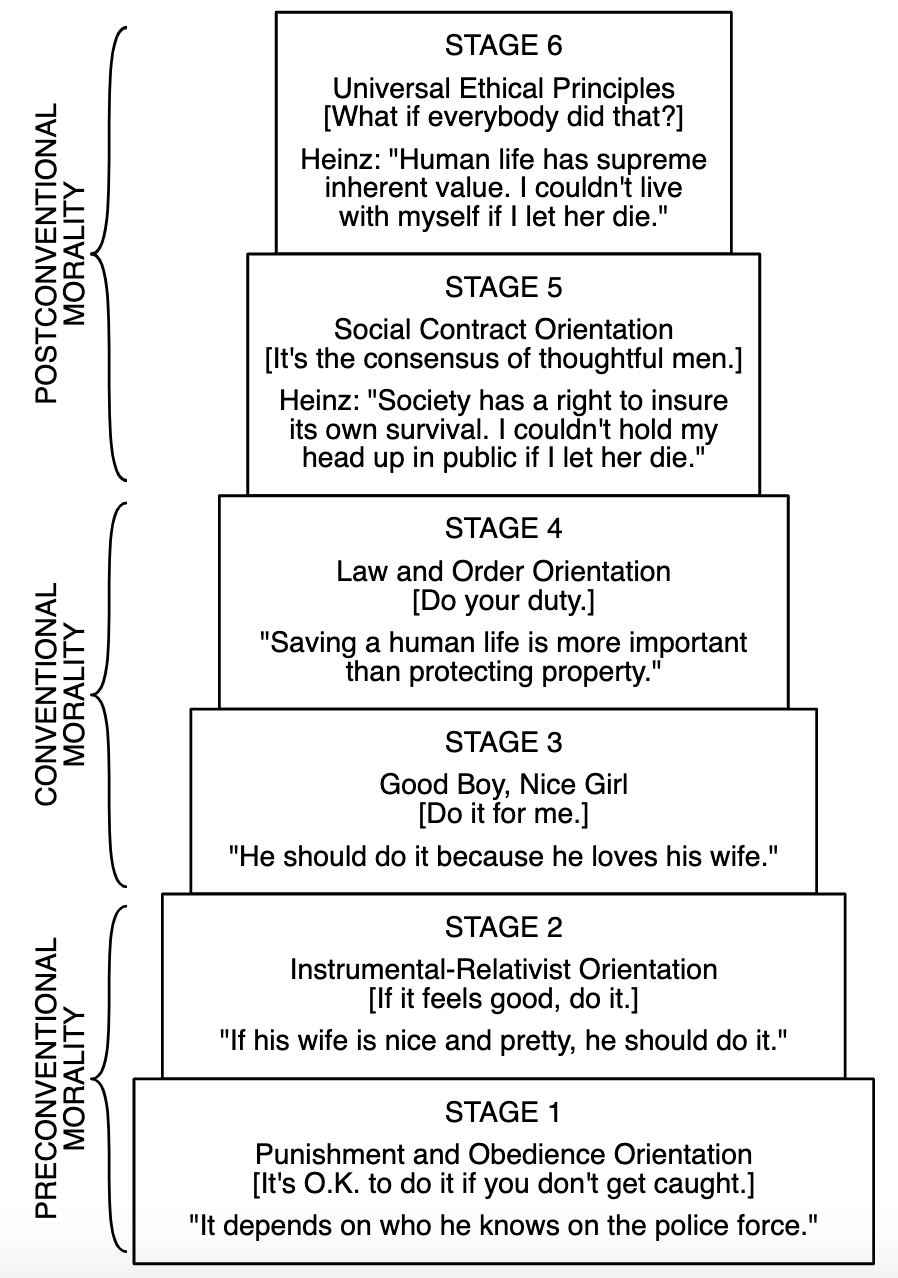

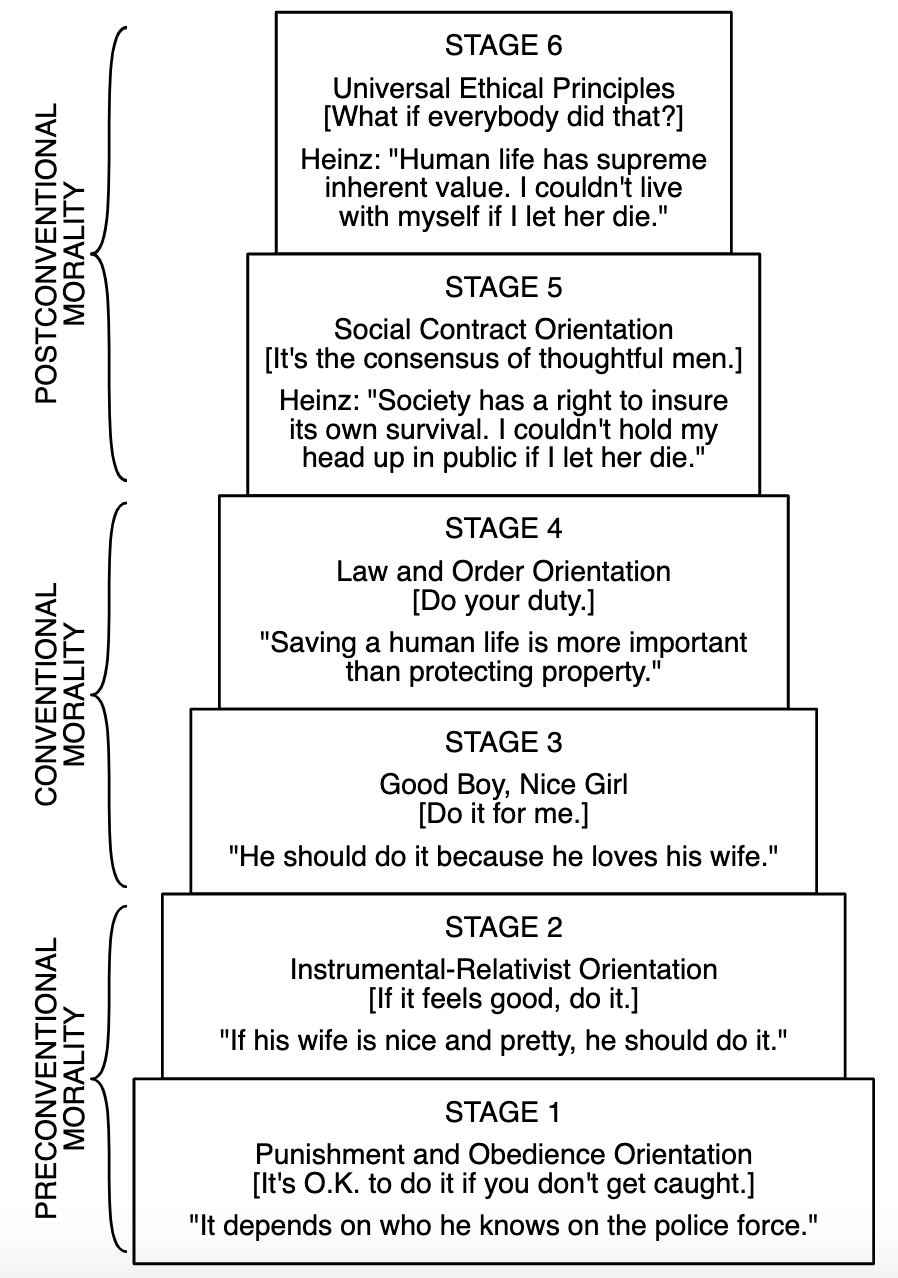

Indeed, doing the right thing and following the rules are often divergent. Kohlberg’s Stages of Cognitive Moral Development provide a fascinating framework through which to view this. The CMD stages Kohlberg created include six stages divided into three levels: pre-conventional (common among children), conventional (based on society and rules), and post-conventional (based on justice and ethics).

(Adapted from www.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_Kohlberg_stages_of_moral_development)

In taking action, Captain Crozier decided that, according to his values, doing the right thing and warning the public about the imminent threat was more important than following the rules. It was more important than his career. He may have broken the rules, but he lived up to his own values, rising to the post-conventional level of Kohlberg’s cognitive mental development chart. I hope Captain Crozier gets reinstated. I hope he can continue to lead his crew and set an example of leading in crisis—decisive, altruistic, compassionate, and brave.

My friend and colleague Josh Selekman* agrees that in times like this, the demonstration of courage should be rewarded and not punished. He mentions a Theodore Roosevelt quote from his speech “Man in the Arena” at the Sorbonne, Paris, April 23, 1910. While not quite gender neutral, the quote otherwise captures the essence of leadership in this moment.

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

Captain Crozier is just one of multitudinous leaders fighting the COVID-19 pandemic. First responders and healthcare workers are on the front lines, putting other people’s lives ahead of their personal benefit. Yes, the medical professionals took the Hippocratic oath to save lives, but they go above and beyond in their daily work and leadership. The angels and superheroes of a crisis—firefighters, first responders, healthcare workers, and educators—are hard at work and for many of them existing irrefutably in that post-conventional level.

One would hope, of course, that politicians also set personal gain aside in times like these. Some politicians are rising to the challenge. Andrew Cuomo, New York’s governor, has been serving up doses of ‘tough love’ during his daily briefings and other communications about the virus. His signature style, compared by the New York Times to a hammer battering nails, is not motivated by politics, power, or self-gain. Instead, he is trying to do the right thing with as much compassion as he can muster. “Facts are empowering,” he said in a March 26 tweet. “Even when the facts are discouraging, not knowing the facts is worse. I promise that I will continue to give New Yorkers all the facts, not selective facts.”

In smaller businesses and large organizations, acts of extreme value-based leadership occur every day. Josh and I discussed examples we observe and stories we hear from HR colleagues; we talk about the leaders in those respective organizations that are stepping up and leading through crisis and doing the right thing while remaining compassionate and authentic. We proudly point out that those are often clients and friends—leaders who operate at the post-conventional levels and “do the right thing” every day to keep their companies operational, to get the critical product or service to the customer, to ensure there is food, electricity, and internet for the millions of us working from home.

Divided Together

“It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.” – Antoine de Saint-Exupery, The Little Prince, 1943 (translated by Katherine Woods)

In the age of COVID, the holidays, including Virtual Passover, come and go. As I reflect on the meaning of the holidays, I think about those who, through the years, took action to save others’ lives while risking their own. In biblical times, Moses faced a Pharaoh to get the Israelites out of captivity.

“My favorite Passover story is after the Israelites flee Egypt and go across the Red Sea that God parted for them,” Josh tells me, “only to then have many others perish when the Sea came back together. Moses then hears God crying and asks God why, saying, ‘Your chosen people are now safe and free.’ God’s response, while pointing at those in the Sea who did not survive, was, ‘They are my people too.’ The clear message is we are all God’s children. Regardless or one’s religion or political affiliation, including agnostic and atheists, the message is the same: We all matter and we’re all in this together.”

There have always been those who did what seemed unthinkable and impossible, risking their own lives so others could keep on living. There are no ‘rules’ to go by; sound decisions have to be made fast, and the way they land is not always easy to predict. This also applies to leaders in today’s organizations who, while being guided by the core organizational values, go above and beyond in scale and impact as compared to what has been done or tried before. “The better leaders step up and learn from times like this and encourage others to do the same,” agrees Josh. “In addition, the better leaders are authentic—they own their decisions and acknowledge when they could have done better.”

There is nothing stable left except us. The only constant is our moral compass. We look inside ourselves guided by our values and try our best to do the right thing. Then, we realize we’re not alone—there are many of us who share the same values. We will get through this together, and we will be better for it.

***

This article is a collaborative effort between Josh Selekman and me. Josh and I are both passionate about leadership development in organizations. This article reflects our thoughts on some of the many facets of value-based leadership during this pandemic as we begin poking at the relationships between leadership, values, and how leaders make decisions and take action in crisis.

References

Kohlberg, L., & Hersh, R. H. (1977). Moral development: A review of the theory. Theory into Practice, 16(2), 53-59.